This is book No. 30 on Paul French’s Ultimate China Bookshelf.

Blurbs:

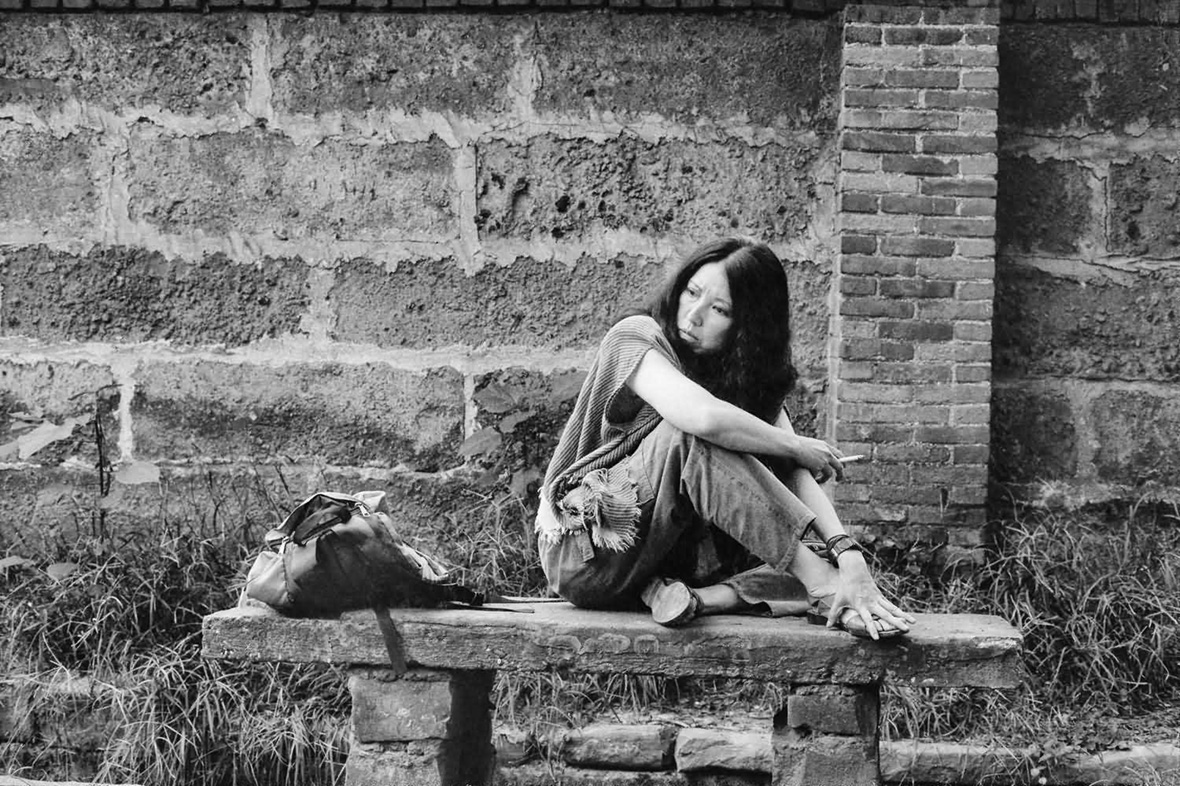

“Hypnotic…A record of one person’s fierce refusal to follow a path laid down for her by the rest of the world.”

—Tash Aw, Paris Review Books of the Year

“Has endured for generations of young Taiwanese and Chinese women.”

—New York Times

“A remarkable and brave book. Sanmao was a freewheeling feminist who broke all the rules and did so with a gleeful, mischievous smile.”

—South China Morning Post

“Reading their stories on this rain-swept island, far from either Taiwan or the Sahara, what seduced me most was the combination of Sanmao’s voice and her indomitable spirit — a spirit that manages to reconcile her dream to be ‘the first female explorer to cross the Sahara’ with the reality of the grinding hardship of settled life in a wasteland.”

—Spectator

About the author:

Sānmáo 三毛 was the pen name of Echo Chen Ping (born Chén Màopíng 陳懋平; 1943–1991), a Chongqing-born Taiwanese writer and translator. She adopted the pen name Sanmao from the famous Chinese cartoon character (the name literally meaning “Three Hairs”), identifying with the child wandering the streets, struggling to survive. She decided she wanted to faithfully record the lives of ordinary people whose voices so often went unheard.

Her family moved to Taiwan in 1949 to avoid the communist takeover of the mainland. She was a keen student of the contemporary Chinese vernacular novelists — Lǔ Xùn 鲁迅, Bā Jīn 巴金, Lǎo Shě 老舍, etc. — and of artists, particularly Picasso. A nasty teacher caused her to drop out of school early, after which she was home-schooled in English, classical literature, piano, and painting. She attended Taipei’s Chinese Culture University.

At 20 she moved to Madrid and met a Spanish man whom she would marry in 1973 after an earlier, German, husband died young. She and her Spaniard husband traveled to the then Spanish-controlled Western Sahara. Stories of the Sahara established Sanmao as an autobiographical writer with a unique voice and perspective, with the book being praised and selling well in Taiwan, British Hong Kong, and China. She went on to write additional books, both about the Sahara and Spain’s Canary Islands. Sadly, her second husband drowned in 1979. Sanmao returned to Taiwan and then traveled to Central and South America on commission from Taiwanese publishers.

In the mid-1980s, she returned to teach at Chinese Culture University on Yangmingshan. She eventually published more than 20 books, translated many Spanish graphic novels into Chinese, and wrote several film scripts (including the much-praised Red Dust, 1990). Sanmao committed suicide at just 41 in 1991. The English edition of Stories of the Sahara was re-released to a new audience some years ago, giving Sanmao a new group of fans.

The book in 150 words:

Sanmao’s Stories of the Sahara (translated by Mike Fu) is part travelogue and part memoir. With her Spanish husband, José (María Quero y Ruíz), Sanmao moves to the Spanish Sahara in the early 1970s, “inexplicably drawn towards that vast and unfamiliar land.” Her experiences are both awe-inspiring and depressing; she was accepted by the Sahrawi community in El Aaiún (Laâyoune), sometimes ebullient and welcoming, sometimes distrusting and resentful. The desert fascinates her — its vastness, cruelty, implacability. Sanmao describes moments of love and tenderness, with José, Spanish expatriate friends, and Sahrawi neighbors, as well as moments of isolation and loneliness. Ultimately, she begins the sojourn in an almost hippie-like hopefulness, though ends it as the country sinks into a bloody independence struggle from Spain, Morocco, and Algeria. Throughout, Sanmao’s prose (translated into English by Mike Fu) is highly descriptive, often wistful, plays with legends and ghosts, and is highly self-critical and self-revelatory.

Your free takeaways:

We reside on the peripheries of the small town El Aaiún. Few Europeans live here, and José and I take great pleasure in getting to know the locals. The majority of the friends we have made here are Sahrawi.

Afeluat was our beloved friend, a young policeman. He had received a high school education, then ended his studies after becoming a police officer. He had a childlike face and a mouth full of white teeth. People were drawn to his kind and sunny disposition, not to mention his sincerity. In town, bombs were going off frequently these days, while business bustled on as usual. Everyone was talking about the political situation, consciously or not.

On the road we saw lots of military convoys driving into town. The government buildings were tightly enclosed by barbed wire. A huge crowd was queuing patiently at the tiny airline office. Suddenly a group of journalists I didn’t recognize caused a commotion by rushing forward like a bunch of hooligans. The anxious racket cast an ominous cloud over this once peaceful town. A storm was brewing.

Once we got down from the roof and took another look at the goat, not only was this prisoner of war not bleating, it looked like it was smiling. I lowered my head to take a closer look – and my God! The nine bonsai plants, twenty-five leaves in all, that I had worked so meticulously to cultivate over the past year, had been clean eaten away.

Why this book should be on your China bookshelf:

The original Chinese-language edition of Sanmao’s Stories of the Sahara was incredibly popular in Taiwan and Hong Kong, and throughout China. Chinese social media expert Manya Koetse, watching the continued attention paid to Sanmao on Weibo, has called her “one of the first Chinese mass media celebrities.”

It is hard to think of a more self-critical and self-revealing piece of writing from a Chinese woman to appear in the late 1970s on the mainland, and it seems to still resonate today. Upon publication of the English translation, the New York Times saw it as a book popular with many Taiwanese and mainland Chinese women eager to escape “social norms.” Of course this is partly true, but we should not overlook the fact that Sanmao is that rare thing (rare at least in the 20th century) of an intrepid Chinese woman travel writer, and that, even judged against her male and female peers from around the world, her writing is gripping and immersive.

Given the times and trends of the period, Sanmao has a tendency to “exoticize” the Sahara and the Sahrawi people (for more on the Sahrawi and the Sahara, Barry Cunliffe’s new book, Facing the Sea of Sand: The Sahara and the Peoples of North Africa, is a good introduction). Yet to a generation of readers just emerging from the Cultural Revolution and the harsh asceticism of the deep Mao years, we can surely understand what a profound and exhilarating experience reading Sanmao must have been. For those feeling isolated and unable to travel themselves, the idea of such unbridled wanderlust and such a contrasting landscape and culture must have been thrilling.

Sanmao herself also suggests a very different type of Chinese woman to the stereotypes of the time, and even later, and perhaps today. She is not without her traditional concerns over the opinions of her (admittedly very liberal) parents in Taiwan, yet she is without doubt a “free spirit,” following her own path whether it be in love, travel, or lifestyle. At one point in the book, Sanmao and José are disparaging of contemporary hippies (Western Sahara was the very end of the North African “hippie trail” in the 1970s), yet they have elements of the subculture themselves in their somewhat freewheeling lifestyles and approach to relationships, marriage, and social interactions. In Stories of the Sahara, Sanmao undertakes a personal journey to a remote location that seems unimaginable to her original readers.

Stories of the Sahara has sold over 15 million copies. But what do readers today take from Sanmao? Is she simply reduced to a curiosity piece of 1970s travel writing? The filmmakers Ana Pérez de la Fuente and Marta Arribas made the Spanish-language documentary Sanmao: The Desert Bride (Sanmao: Le Novia del Desierto). In it they discuss Sanmao’s legacy from the 1970s to the present day, what they describe as her “canonization” and the problems around that, raising questions about visibility, sociocultural (mis)understandings, and cultural power. Not least perhaps for those of us interested specifically in China, we can note the perhaps problematic issues around Sanmao traveling from an undemocratic Taiwan at the time to an undemocratic Francoist Spain (albeit in its last gasps) and thence to one of Spain’s most contentious and restive colonies.

It is to Sanmao’s credit that (and again, remembering that she is writing in the 1970s) while often relishing the difference and the “other” of the Sahara, she is not blind to the poverty, colonial oppression, or the gathering storm of independence around her. Indeed, it is that slow build from arrival, initial fascination, early friendships, and cultural missteps to finding herself in a terrible and dangerous fratricidal anti-colonial struggle that makes Stories of the Sahara so compelling.

Next time:

Enough global roaming for a while. Next time we move on to a different subject — one that is both historic and contemporary — Hong Kong. First we consider its history, then its particular role in World War II, and finally the events of the “handover” in 1997 that completed one long cycle of colonialism while starting the next, and current, cycle of post-colonial existence.